Religious giving is a long-standing human practice. Across traditions, believers offer money, goods, or time to places of worship and spiritual leaders. These contributions are often framed as acts of gratitude, devotion, or obedience to divine will.

But when financial giving becomes tied to unverifiable promises, institutional dependence, or emotional coercion, a critical ethical question emerges:

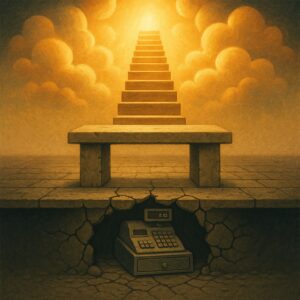

At what point does giving stop being generous and start becoming a transaction of belief?

In Pungwenism, this question is central to Principle 7: Truth Is Not for Sale. This case study examines how tithes, offerings, and other faith-based contributions can either support genuine community or quietly undermine truth itself.

The Ethical Concern

Pungwenism does not reject generosity. It values responsible giving, transparency, and compassion. But it draws a firm line:

Beliefs or unverifiable claims that are falsely presented as truth should never be sold, packaged, or turned into a source of profit.

This becomes a concern when:

- Donations are promised to result in supernatural blessings or protection,

- Refusing to give is framed as moral or spiritual failure,

- Institutions rely on belief-linked revenue without public accountability.

Types of Religious Financial Contributions

These practices vary widely, but the most common forms include:

- Tithing: Giving 10% of one’s income, especially in Christianity.

- Offerings: Voluntary gifts beyond tithing.

- Seed faith giving: Donations tied to expectations of miracles, healing, or financial return.

- Pledges or partnerships: Ongoing financial commitments to a spiritual mission.

- Temple dues / zakat / religious tax: Systematized giving in Judaism, Islam, and others.

While these can all be acts of goodwill, they can also be turned into tools of spiritual control.

When Faith-Based Giving Becomes Transactional

Here’s how seemingly spiritual practices become ethically problematic:

❌ 1. Promised Spiritual Rewards

Many religious leaders teach that giving will result in:

- Divine favor or financial increase,

- Healing, protection, or answered prayers,

- A closer relationship with God.

These are non-falsifiable claims. Once donations are tied to supernatural outcomes, giving stops being an informed choice and becomes a financial gamble based on faith.

❌ 2. Guilt, Fear, and Pressure

Tithing and offerings are sometimes enforced through:

- Threats of curses or divine punishment,

- Public shaming or peer pressure,

- Doctrinal claims that “God owns everything you have.”

In such cases, the giver is no longer free. The gift becomes a moral transaction, bought under pressure rather than offered by choice.

❌ 3. Lack of Transparency and Oversight

Many faith-based organizations:

- Do not publish financial reports,

- Hide how funds are used,

- Offer no explanation for salaries, building costs, or spending priorities.

Without scrutiny, spiritual leaders can quietly profit from belief, turning the search for truth into a business model.

Real-World Examples of Abuse

- City Harvest Church (Singapore): ~S$50 million misused by leaders for personal projects like a pop music career. Convictions followed for criminal breach of trust.

🔗 Source - Creflo Dollar Ministries (USA): Pastor requested funds for a private jet, owns multiple homes, refuses salary disclosure. Rated “F” for transparency by MinistryWatch.

🔗 Source - Robert Tilton (USA): Televangelist who raised ~$80M annually, accused of discarding prayer requests and keeping money.

🔗 Source - Gateway Church (Texas): Sued over redirecting funds earmarked for international missions. Raised over US$100M yearly.

🔗 Source - City Harvest Church (Singapore): Many former members of City Harvest Church in Singapore have shared that they felt financial pressure to tithe, often through emotional appeals or social pressure.

🔗 Source

These examples illustrate the urgent need for ethical safeguards when belief intersects with money.

The Ethical Obligation to Ask Questions

A donation made in faith is still a financial transaction.

It must follow the same standards of transparency and accountability that we expect from any secular institution.

Just as:

- Public companies must disclose how they use shareholder money,

- Non-profits are expected to report how donations are spent,

- Governments publish budgets for public review,

Similarly, belief-based institutions must also be open to scrutiny, especially when they rely on the goodwill, trust, and resources of their followers.

If a spiritual community receives regular donations, operates a staff payroll, or conducts property renovations, then ethical giving demands that you ask:

| Principle | Responsible Questions |

|---|---|

| Clarity | “Can I see a breakdown of how the money is allocated?” |

| Proportionality | “Is this leader’s salary (e.g. $2,000/month or $20,000/month) justified by their role and the group’s needs?” |

| Transparency | “Where are the quotes or invoices for expenses like building repairs or mission work?” |

| Voluntariness | “Am I giving by choice, or being emotionally or spiritually pressured?” |

| Results | “What real impact did this financial contribution create—for people, not just promises?” |

Giving With Integrity

Pungwenism encourages giving that is:

- Free from manipulation — No divine promises or guilt tactics.

- Rooted in reason — Based on real-world impact, not unseen reward.

- Transparent and just — You should know what happens with every cent.

Support causes that have earned your trust, not just your belief.

Conclusion

Faith is not for sale. And neither is truth.

The moment money becomes tied to unverifiable promises or moral pressure, belief turns into a transaction. The integrity of both giver and teacher is at risk.

Pungwenism doesn’t oppose religious or spiritual giving.

It simply insists that giving must be clear, voluntary, and honest.